What does the Trump victory mean for the UK economy?

SPECIAL ANALYSIS: In a special report for Recruiter, Julius Probst looks at the effects of a Trump presidency on the UK.

Even though Europe was very much aware of the possibility, Donald Trump’s re-election as president of the US created a shock-and-awe moment. While large exporting countries like Germany will see their economies suffer in the case of a trade war, British deindustrialisation, once seen as a major weakness, might now be a relative advantage. As the UK has become a service-exporting superpower, its economy will be more immune from Trump’s tariffs.

Stagnant but with upside potential?

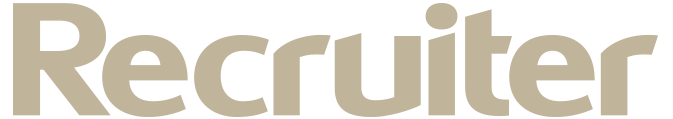

The UK economy has faced various headwinds over the last couple of decades, starting with austerity after the Global Financial Crisis, followed by Brexit. The recent recovery from the pandemic has been anaemic as well since high interest rates to contain inflation are now stifling economic growth. Payroll employment growth initially surged throughout 2021 and 2022 but has also been completely stagnant this year. Per capita GDP is no higher than in late 2019.

The Autumn Budget from the Labour government is setting the economy on a different path. Higher government spending and higher taxation are to be expected. The hiring outlook will remain challenging at first because of the increase in employers’ National Insurance Contributions and another minimum wage hike.

Nevertheless, economic growth in the UK has defied forecasts of a long and scarring recession. Relatively speaking, the UK has large upside potential if Labour were to finally fix the country’s most severe bottlenecks (housing and infrastructure). Unlike continental Europe, the UK is uniquely positioned to come out of a potential trade war relatively unscathed. There is even a chance that the UK might indirectly benefit from some of Trump’s policies.

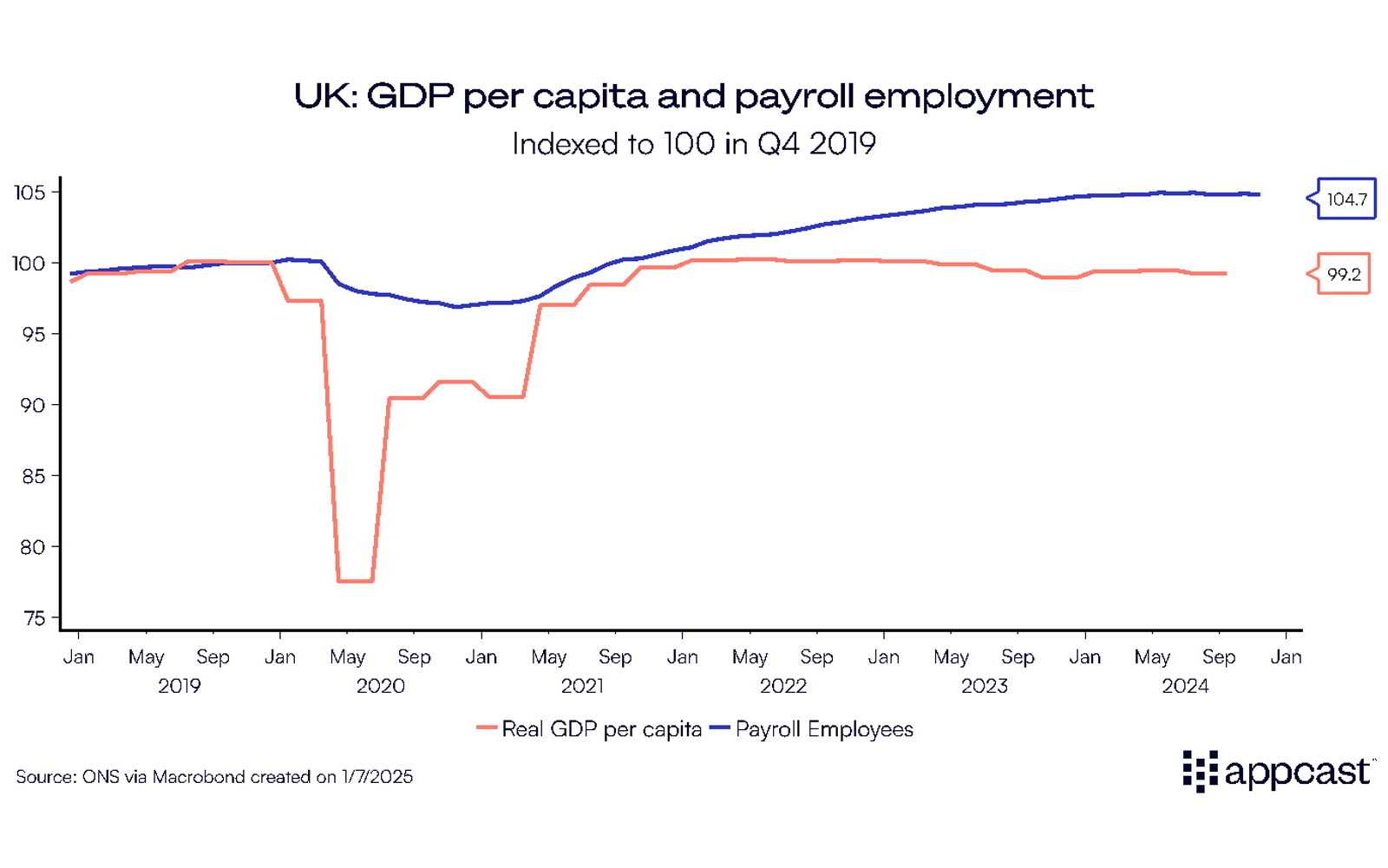

The UK is benefitting from its status as ‘service-exporting superpower’

While continental Europe continues to specialise in the production and export of manufactured goods (think cars and machinery), the UK economy has become increasingly focused on services. In fact, more than 55% of the UK’s exports to the rest of the world are services, whereas for other large, advanced economies, that value typically is below 30%. The UK export more services than goods to the US (close to $90bn, or £73.8bn, compared to about $65bn). And since there are no physical goods crossing borders, service exports are not subject to tariffs.

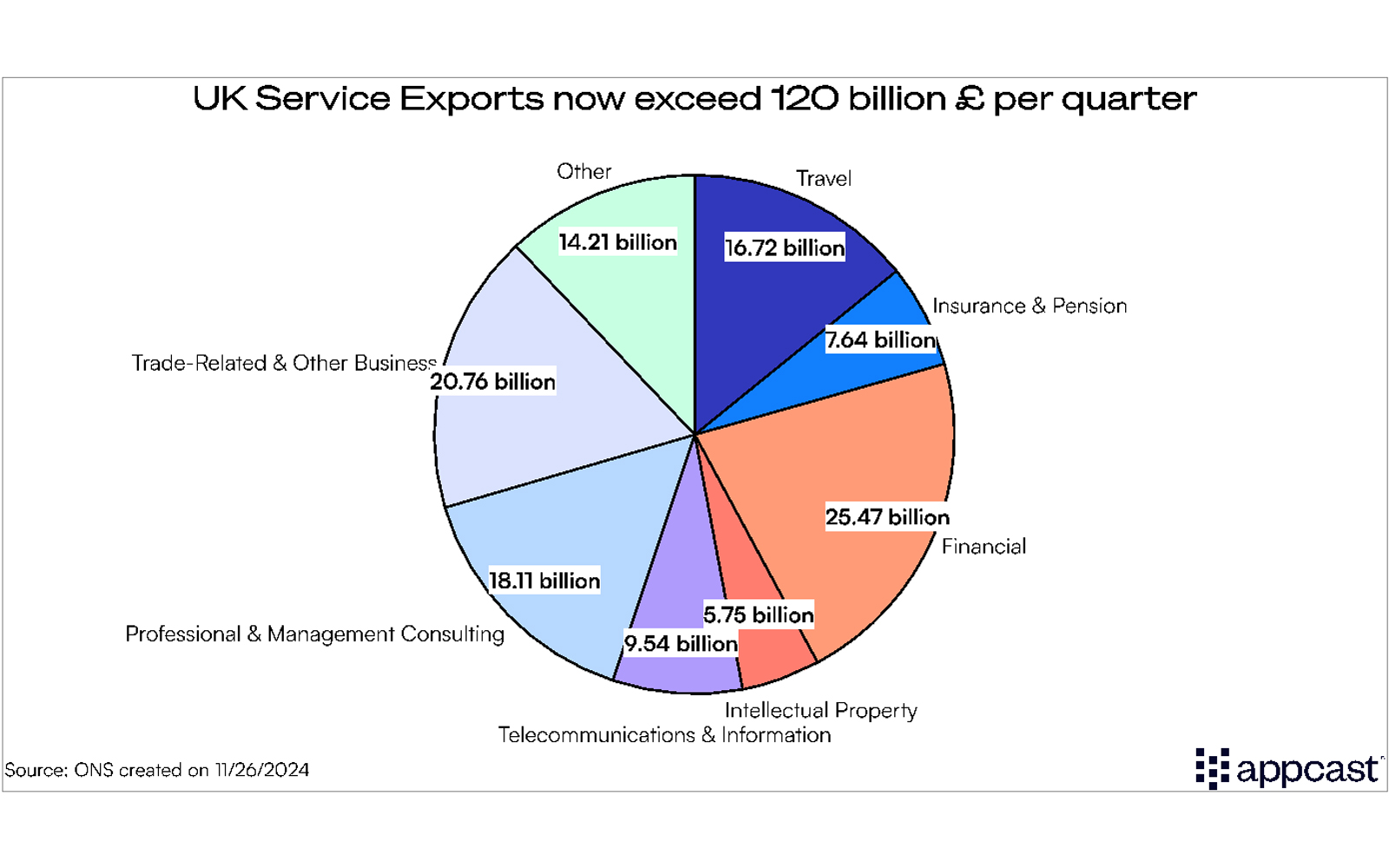

The pie chart below breaks up the UK’s service exports into different categories to give you an idea of what we are talking about.

- £25bn in quarterly exports to the rest of the world are coming from the financial sector. This includes fintech solutions (using Revolut or Wise for cross-border payments), investment banking services, asset management, merger and acquisition advisory services, etc.

- Some £18bn are coming from professional and management consulting services.

- Accounting and auditing services are another significant UK export.

- £17bn comes from travel (tourism is classified as an export).

The UK economy, with London at its centre, is basically an island of lawyers, bankers, and consultants who are offering their services to clients abroad. All these activities have become economically more meaningful than the exports of actual goods, which has completely stagnated in recent years due to Brexit. The fact that the UK has become a service-exporting superpower is now playing to its strength since these activities will be exempt from Trump’s tariffs.

Downside risks are an even stronger dollar and geopolitical shocks

The dollar has already appreciated against all currencies following the US election and might see further gains as Trump’s economic policies are expected to be inflationary. A stronger dollar is typically associated with weaker economic growth in both emerging and advanced economies. It also might force the Bank of England into keeping interest rates higher for longer because of inflationary pressures coming from commodity prices (usually invoiced in dollars).

Another big concern for the UK and Europe in general under a Trump presidency is the escalation of geopolitical shocks, such as a continuation of the wars in Ukraine and the Middle East. Such shocks are inflationary in nature and would leave central banks with no choice but to keep interest rates higher for longer. Both the stronger dollar and geopolitical shocks are thus detrimental for growth, inhibit job creation and negatively impact the hiring outlook.

What does that mean for recruiters?

The effects of Trump’s presidency will be felt unevenly across Europe. The UK economy will be more resilient than continental Europe because the UK and the city of London have become a global service hub. More than half of the country’s exports are now services that will not be subject to tariffs. Policy makers in the UK should, therefore, focus on the country’s competitive advantage in service exports.

In terms of the hiring outlook, it is too early to tell how the different US policies will play out. The stronger dollar is a negative for the UK economy, as are tariffs applied to the exports of goods. However, a special trade deal between the two countries could come at the EU’s expense and might provide the UK economy and labour market a well-needed boost.

Julius Probst is labour economist at Appcast (part of The Stepstone Group).

• Comment below on this story. Or let us know what you think by emailing us at [email protected] or tweet us to tell us your thoughts or share this story with a friend.